There were two girls about my age and two below school age, plus a baby boy.

New Family

They were very different. The father was a new cowman. His farmer employer could not get his cows ‘TT Attested’, which meant tuberculosis free, until this new cowman came. The family lived in the room in which we’d had chapel services. It had one thing I really loved, a piano. I played it, well I played the notes each time I went and the more I touched those notes, the more I wanted one. The mother said I could play as much as I liked. I truly think she had so much to do that she hardly noticed. She very willingly worked hard to keep them all clean and fed. The last person she thought about was herself.

I felt rather sorry for the little girls because they had no dollies. My dollies had been so important to me that I thought this absence really tough. Mine were still sitting at home in my pram. I asked my Mum if I could give them away and she said that I could. I gave them Ena, a tall rag doll, a good 75cm long, Peggy, with a cloth body who had a pottery head through which you could thread a ribbon and Pamela a China doll. All of them were dressed. I took my gifts over. The children were very pleased and I was happy. A few weeks later I was in the house again and enquired after them. I was horrified to find they had all been destroyed, not maliciously, just not treated with care. Their mother told me, “That rag one did very well. It lasted a fortnight”.

I rapidly realised there may have been a dearth of dolls because none lasted very long. I was shaken to learn that things could be treated so carelessly. Good job the piano was robust! Perhaps it was disinterest, if so I hoped it would remain that way. None of these feelings did I show or let on to my Mum because she would have been shocked and I deemed it politic to keep schtum.

The Barrack Square

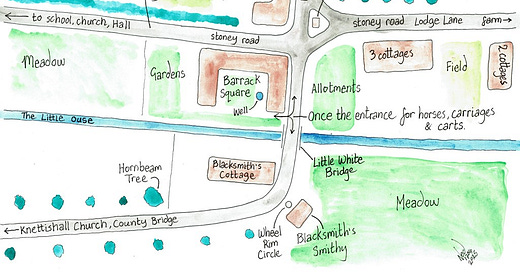

Our little hamlet was once a stopping place on the way from Bury St. Edmunds to Norwich via Harling. There was an old coaching inn, reputedly called ‘The Gatehouse’. There were four gates, so it became known as Gatesthorpe, then Gasthorpe, hardly an improvement one might think, but quicker to say. The Gatehouse had rooms and stabling, the whole making nearly a rectangle if you include gardens. There was an entrance for the carriages and horses to get to the stables at the back. The housing part faced the road while the stabling made up the remainder of the buildings. Both bits had been converted into nine cottages and the whole became known as the Barrack Square.

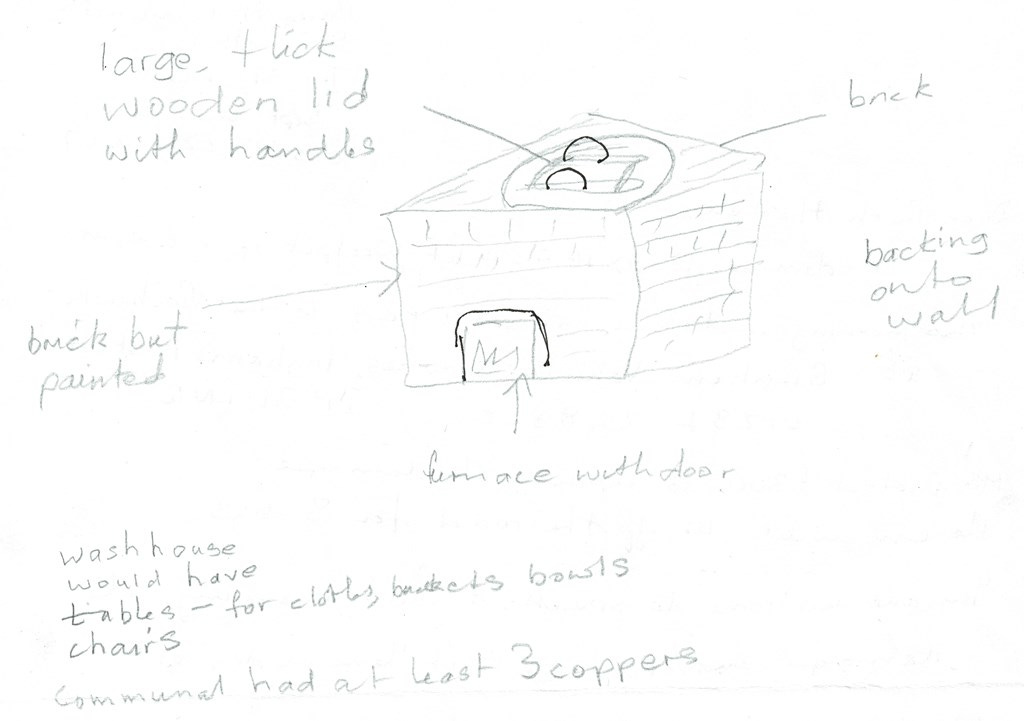

On entering from the road you saw a large communal lawn with a communal well in the right hand corner. Each cottage had a small front garden where flowers were grown and a large piece of garden round the side and back for vegetables. Many tenants also had an allotment away from the house for more vegetables, so what with working on the farm as well there were few idle hours. There was a large lawn with cottages on three sides. The fourth side had gardens separated from the lawn by a fence about a metre tall. In the far corner there were sheds, a battery of loos and a communal washhouse which had at least three or four coppers with built in furnaces beneath; a copper being a big copper bowl positioned over a wood and or coal furnace and the whole encased in brick. The washing could be done and chat at the same time.

I wonder if the copper is higher than pictured above, but perhaps I was small and the copper top appeared higher to my then tinier self. This is my sketch of a ‘copper’. It’s faint to see and read the notes, but perhaps useful to include.

Weekends and evenings this place also served as a mild gambling den for young men who would gather for cards. Young girls did not frequent this place as most would be ‘living-in’ servants by that age and others busying themselves with home domestic duties. I don’t recall the young men helping fathers out with gardening, but feel sure they did. We children would go to the washhouse after tea and ‘watch the cards’. ‘The Boys’ as we called them, were never anything but very civil to us. I’m sure that we were very mindful of our behaviour and no bother to them. I don’t recall them using strong or bad language, but we would disappear early for bedtimes, so maybe they let their hair down then. The washhouse was closer and cheaper than going to the pub. The entrance to the Square was another gathering spot for young men. They would lean against the railings which separated the road from one of the gardens.

The cottages in the Square were quite small; each had a lean-to kitchen, some of which had a copper. Each had a living room with a large table in the middle and a blackened kitchen range with both hob and oven. There were several doors, one to the kitchen, one to the Square, at least one to a cupboard and one to the windy (a winding staircase, not to be confused with windy weather) staircase which led to two bedrooms, a landing and perhaps an attic.

Gasthorpe Bridge And The Blacksmiths

Just down the road from the Square there was a small bridge over a stream, another favourite play place. Beyond the bridge was a very sharp bend in the road. On one side was a long thatched cottage standing at right-angles to the road. It backed straight onto a meadow, but in the front there was a very large garden. The meadow went right to the walls of the cottage, but all round the rest of the large garden were well tended hedges. In the cottage lived the almost retired blacksmith with his elderly, fragile wife. Sometimes she would walk down the road and we would exchange conversation. She never made much sense and we found it very hard not to giggle. She seemed as from another era.

Her son lived in the Barrack Square with his wife whom we knew as Party, but always called her by her proper married name, Mrs. Cutter. Her real name was Partridge and we children liked her because she was so happy with a ready smile. She used to daily carry hot dinners to her in-laws on a tray covered with a nice cloth. In later years Party was in and out of psychiatric wards having unpleasant treatments. They had no children. Perhaps her life was duller than she could bare. Party’s husband Ted ran the blacksmith business. He too was very nice to us.

When he fixed metal runners to our wooden sledges he only charged a tiny amount. The furnace had bellows which we would pump which caused the embers to turn from grey to red and flare up while Ted and his father held straight lengths of metal in the heat. They would then knock them into the required shape, often horseshoe shaped for the many horses they shod. The metal was dipped into a rectangular bath of cold water at the foot of the furnace, both to retain the new shape and enable them to look carefully for readjustments where needed. It was fascinating to see a shoe fitted against a hoof, then modified and the nail holes punched. The horses sometimes turned their large heads as if to see what was going on. Each one would be loosely tethered while the shoeing was carried out. It was a warm welcoming place and we were never told to go away. Ted was quiet and said but little, but what he did say was always friendly. We never had the impression of being in the way. His sister was a teacher and lived away. Sometimes, with her son Brian, she would visit and stay in the blacksmith’s cottage and Brian would come into the smithy. His mother would always go to see my mother.

Eventually, after the elderly couple died, horses went out of fashion, tractors came in and Ted and Party went to live elsewhere. A new estate workman moved into the blacksmith’s cottage for some years and after he went it was sold and remained empty for half a century. The smithy itself was skilfully converted to a bungalow. The two twisted chimneys, similar to those on Hampton Court Palace, were carefully drawn, taken down brick by brick, then rebuilt in the same pattern. The flint walls remained as did the concrete wheel shape in the front used for putting metal round wooden wheel rims. The interior was gutted and completed modernised. My parents went to live there when they retired from the shop and my children would run around the metal floor plate; though I am debating with my son whether it was concrete or metal.

Farm Road

Opposite our Post Office house there was a stony road, which had a farm house and two cottages at the end of its half mile, but a little way up, there were three thatched cottages in a terrace. Each had its own well and enormous garden, an outside loo and an outhouse. Inside there was a living room with a black kitchen range providing fire, hob and oven. A door led to a windy staircase and three bedrooms. Off the living room there was a big walk-in larder. The middle cottage had no external access to its own back garden, so they had to use their neighbour’s garden or cart things in through the house.

Each cottage in the village had a copper somewhere inside or nearby. It was essential for heating water, for bathing, washing clothes, spring-cleaning or any job requiring plentiful hot water. The water would remain warm for a good 24 hours in those brick surrounded coppers.

Our Shop

Our little shop from some approaches seemed to stand in the middle of the road. We were on a corner where four roads met. The shop faced onto what had been the old Norwich-Bury road. One way it went to Harling and Garboldisham and the other to Knettishall. The road in front went to a farm and the other one to the school, St. Peter’s Church, Riddlesworth and Riddlesworth Hall. Our plot made up a quarter of a circle. On another corner was the Barrack Square. On another some allotments and the fourth was a meadow with a line of oak trees at the edge. A road ran between the line of trees and the allotments, another between the allotments and the Barrack Square and another between the Square and our garden. Harling Lane was between our garden and the meadow.

We had a very large lawn on which we at one time had a badminton court, a massive vegetable garden, fruit trees and a piece of rougher ground on which chickens pecked. At one corner some pig styes and a large outhouse which was later used as a garage.

Considering the small population our little shop was busy. We had a good supply of cigarettes. By some accident the war time allocation to her shop had been given to Mum because she had previously put in an unusually large order for some special reason, so she did relatively well. As well as local trade, lots of lorries used to stop. We opened at 9am while most workers started at 7.30am. Before going to bed Mum would line up cigarettes with the right change for the regulars in the morning. They were lined up on the dresser, a piece of furniture, just inside the road door. 10 Weights (cigarette brand) plus two pence change for Jim, 20 Woodbines and three pence change for Jack and so on along the dresser in the order in which they would knock. We took the money and handed the ciggies back in one movement. It was all most efficient. They would never take extras the previous evening because they knew they would smoke them all.

Continue at:

Gasthorpe Tales 005

https://gasthorpetales.substack.com/p/gasthorpe-tales-005

Previous post:

Gasthorpe Tales 003

https://gasthorpetales.substack.com/p/gasthorpe-tales-003